Vintages follow one another but aren’t necessarily alike, and to grow vines and make wine from their grapes, you need to listen closely to nature. Across the Domaines of Paul Mas, 2023 was marked by extreme climatic conditions, where rains had a dramatic role to play. Thanks to great reactivity by the teams and interventions in the vineyards, to protect and fertilize the vines and work the soils, excellent results in the vats were still able to be achieved.

UNUSUAL CONDITIONS

Winter 2022 brought an end to a dry year where the opportunities to be ‘singing in the rain’ were rare, across all the different terroirs. Here are two examples among the 17 properties spread across the whole of the Languedoc and Roussillon: At Chateau Lauriga, in the aptly names Aspres Roussillonaises, literally “dry lands” in Catalan, only 180mm of rain fell in one year. At Chateau des Cres Ricards, in the Terrasses du Larzac, by the end of September the vines had only received half the usual 500mm of annual rains.

An additional difficulty was that although in some places the first drops of rain of 2023 fell in May, 130mm of rain then fell in the next two months on these lands. This led to humidity which increased the risk of mildew.

Other properties saw long periods of humidity which increased fungal disease risk. In the Limoux vineyards, especially at Chateau Martinolles, the drought which lasted until the end of April was brutally interrupted by rain between 7th May and 15th June. In Costieres de Nimes, at Chateau Oustau Saint Andre, the furthest east of the Domaines Paul Mas, once again the dry, windy winter and spring gave way to a rainy start to summer.

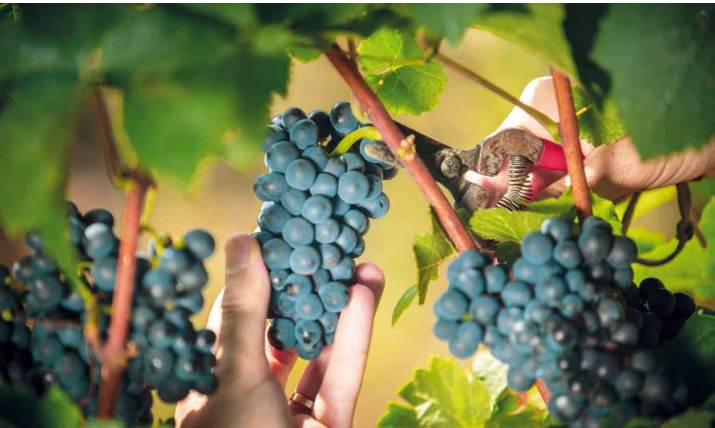

Across the regions, it was therefore necessary to follow the rhythm of the skies. Parasites and other pests do not observe either Sundays or public holidays, so the teams were constantly ‘on the bridge’ to fight the fungal infections. Happily their efforts were not in vain. The harvest was not only saved but in some cases it exceeded that of last year, as was the case for the 50 hectares of organically farmed vineyard at Chateau Oustau Saint Andre. And finally, the last act of a year which was not going to allow any respite to either the vines or those who tend them, certain vineyards saw a hot and dry summer. Two resulting scenarios were: either drought blocked maturation of the grapes, or if the grapes were at a more advanced stage, it became a real race against the clock to harvest before the alcohol levels took off. At Chateau Martinolles, the thermometer went crazy just as the first clips of the secateurs were felt, and it was necessary to harvest at speed, in particular with the Chardonnay.

AT THE RECEPTION, SOME VERY VARIED YIELDS

The weight of the harvest varied according to several factors: Firstly, the terroir itself, which we define by the nature of the soil, the altitude and orientation of the parcels. For example at Limoux, vines planted on the soils with a strong proportion of clay suffered far less than those on limestone. At Montagnac, the vines on the plains coped better with the drought than those on the slopes.

Another essential parameter: access to water. At Chateau Lauriga, where 30 hectares were irrigated this year, the difference was spectacular: 6 to 10 tonnes per hectare for those vines which were able to benefit from irrigation, versus 3 small tonnes ( 7 to 25 hl/ha) for those which had to do without. The same vast contrast in yields was seen at Chateau des Cres Ricards between those parcels which were irrigated and those not. At Chateau Oustau Saint André, on alluvial soils whose ‘pudding stones’ store and share their heat, access to water was key in producing excellent results.

However it’s important to stress that it was still possible to maintain a balanced level of production without the aid of irrigation. The sixty hectares in the Minervois appellation at Chateau Villegly are proof of that.

To achieve this great result, having living and breathing soils is the key. The plough, besides the fact that it limits (in an ecological way) too much competition between the grass and the vine, decompacts the soil. Unlike herbicides, it maintains the soils biological activity, which helps feed the plant. In addition, by cutting unnecessary roots, it forces the vines to dig deeper with their roots to find water and mineral salts.

Once worked, the soils are also fertilised ‘in the old way’ in Autumn and Winter. Additions of manure, organic fertilizers and innoculations of bacteria all bring organic material, more important than ever when periods of drought block the microbial life to the soils. The results are visible to the naked eye and can be also detected on the nose: from the earth comes an aroma of humus (mould). Being more dense, they retain water better. Better nourished, the vines produce a greater volume of grapes.

… AND JUICE OF GREAT QUALITY

In the wineries, the winemakers celebrate in unison the quality of the grapes, which have come in very healthy. Where the volumes are lower, the berries are more concentrated. At Chateau Cres Ricards, the first analyses indicate high polyphenol values which promise structured wines. The blends will be crucial to achieve the balance and attenuate the power of the grapes which came in with high alcoholic degrees. Guillaume Bonnet, the estate manager, admits a fondness already for the Syrahs, which if they looked somewhat sad on the vine, with berries shrivelled by the heat, have turned out ‘incredible’ in the vats.

Hugo Terruel, winery manager of the Nicole and Astelia wineries, also observed grapes with less juice but with balance and good degrees of alcohol, promising powerful, tannic red wines with notes of pepper and spice. On the Conas plain, where the very dry climate is transforming it into the Languedoc’s answer to Napa Valley, even the Merlot were transformed into intense black juice after only two rackings. For the Cabernet Sauvignon, it was necessary to closely watch the extraction of the rich first material to achieve from the start all the sugar, so as not to be confronted with with stopped fermentations. Here, the cellar master has a weakness for the old syrahs from the AOP Languedoc (with a yield limited to 35 hl/ ha) which go into the Chateau Paul Mas.

On the white wine side, the same story: Lower yields but with a higher quality of juice compared to those of 2022, with delicious fruity and floral aromas already showing. The Chardonnay and the Viognier embody exotic fruits such as pineapple and banana, while the Sauvignon shows its thiol profile, even without cold stabilisation. And despite their generous degrees of alcohol, the musts retain their tension.

José Ramos do Santos, Director at Domaine de la Ferrandière, whose 150-plus hectares are planted in an ancient lake-bed, says that 2023 will be an excellent year for the white wines, whether they be Chardonnay, Viognier, Vermentino, Sauvignon Blanc or even Riesling.

At Chateau Martinolles, whose 90 hectares are cultivated on the wooded commune of Saint-Hilaire, the birthplace of French sparkling wines, Bastien Lalauze professes himself ‘very satisfied’ as well with the vintage, in both quantity and quality.

The bubbles, Blanquette and Crémant de Limoux, already show promising aromatics with berry fruits and floral notes. The still whites are also very perfumed, with a good acidity despite the high heat of the summer. The reds are showing very fruity in character and conditions have particularly favoured Pinot Noir. Harvested earlier, with lower alcohol degrees, the skin to juice ratio favours the phenolic extraction with a very attractive colour and pretty fresh red fruit flavours.

So if harvest 2023 has not run in as ordered a way as a musical score, it follows in the continuity of the previous ones, 2019, 2020 and 2022 (2021 being the exception due to frosts which affected up to 70% of the crop). Above all, it constitutes proof that well-orchestrated vineyard management and hard work can result in a concert worthy of praise!